Last week I had the pleasure of speaking at the Transatlantic Dialogues interdisciplinary conference in Liverpool. The conference was jointly arranged by the Ironbridge International Institute for Cultural Heritage at Birmingham University and the Collaborative for Cultural Heritage Management and Policy, at the University of Illinois. There were loads of papers on questions of transatlantic heritage, from the tale of John Quincey Adams as a tourist in Paris to American views on the British Royal Family. My own paper, which I’ve included below, looked at an American tourist in Europe, walking the world of Sherlock Holmes.

In the late 1970s David Hammer, an American lawyer and life-long fan of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, was taking a cruise down the Nile in Egypt. As he admits, Hammer was a particularly fussy customer. After complaining many times about the way he and his fellow tourists were “shepherded” about, one of the tour guides put Hammer on the spot by demanding what type of tour he would like to be on. Hammer suggested a tour of Sherlock Holmes sites in England. This, he claims was the genesis of his series of travel books, in which he told the tale of locating sites of Sherlockian significance across North America, Britain and Europe. One of these books in particular, called A Dangerous Game: Being a Travel Guide to the Europe of Sherlock Holmes, is of interest to us today because of the way in which Hammer’s particular style of travelling and writing shapes the fictional world of Sherlock Holmes into a form of intangible, transatlantic heritage.

Hammer himself was probably the first person to make this point about his travel books. In his memoir, called, The Game is Underfoot, he writes that, “I never really believed that Holmes had lived. I still don’t, but I do believe that he was real; so real, in fact, that if he has not become a figure of history, he has of heritage, which surely constitutes a significant form of reality. Besides, as I once wrote in the same context, there is meaning in myth and fact in fiction”. But what kind of ‘heritage’ do the Sherlock Holmes stories constitute? Robinson and Andersen, in their exploration of literary tourism as the interaction between the art of literature and the practice of tourism, specifically pinpoint heritage as one way literature has been commodified for tourist experiences. They argue that literature possesses, “some sort of public legacy expressed in emotional as well as spatial terms”. In this way, literary works can be seen as “cultural reference points that sit with conceptions of social and cultural identity, ideas and ideals of nationality and nationhood, and popular discourses of historical development”. It is this interaction between cultural reference points and these conceptions where the work of literary heritages takes place.

Literary tourism’s interaction with literary heritage appears, to Robinson and Andersen, to focus in part on the idea of re-living an imagined or half-remembered, past. As they write, “nostalgia is important here and it seems like literary tourism increasingly plays to an audience that wishes to travel in time as well as space”. Reading the first pages of Hammer’s Dangerous Game it would seem he agrees. Because he says that Sherlockians, “are essentially time-travellers, committed to another time, and perhaps worse, to places where we never lived, and for some, have never seen”. This interplay between past and present is particular interesting in relation to literary heritage given the difficulty in discerning the boundary between fact and fiction in literature – and in the performance of literary tourism. Robinson and Andersen draw this boundary between tourists motivated by a biographical interest in the author and those motivated by the literary work itself and exploration of its fictional world.

So, with all this in mind, today I want to read Hammer’s travel guide to Europe as a text that re-lives an imagined past, as a form of intangible, Sherlockian heritage. I will explore how Hammer’s writing places the fault line between fact and fiction, the past and present, at unusual and unexpected places. And I will show that the result, which is a blending of fact and fiction, history and tourism, draws on Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, on historical artefacts and on Hammer’s own experiences moving across Sherlock Holmes’s Europe.

Holmes’s Fictional World

At first glance, Hammer’s travel writing, like many classic literary tourists before him, appears to put great value on the fictional world he wants to explore. Indeed, A Dangerous Game is a very good example of Hammer’s work for our purposes here, because unlike his earlier travel books, the first two sections of this book, taking up almost half the pages, are structured by the events of Doyle’s 1891 story The Final Problem. The book is filled with chapter titles such as, ‘The Flight’, ’Still Deep in Snow’, ‘A Charming Week and a Lovely Trip’, and ‘I Found Myself in Florence’. These refer to lines or events from two of Doyle’s stories The Final Problem and The Adventure of the Empty House. In these chapters, Hammer follows Holmes and Watson’s footsteps across Europe as they flee from Moriarty in London, only to meet again with Moriarty, and with disaster at the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. By structuring his text in this way, Hammer seems to be following the a practice common to other Sherlockian guide books, where Doyle’s stories take centre stage and real-world sites or events are negotiated through meanings derived from those stories.

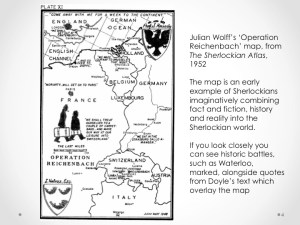

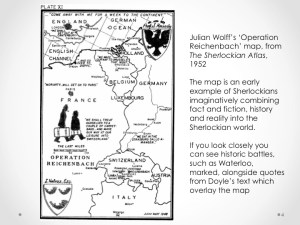

Hammer’s work draws on a rich history of Sherlockian fans interpreting the world through meanings found in the Sherlock Holmes stories. Julian Wolff’s 1948 map, Operation Reichenbach (above) is a good visual example of this practice. Like Hammer, Wolff’s map is structured by the events of The Final Problem. Like Hammer, Wolff marks Holmes and Watson’s path across Europe to Switzerland. Place markings such as Brussels or Paris are justified by the inclusion of direct quotes, which indicates that they are referenced in the story. Over Paris, for example, is written the words, “Moriarty… will get off in Paris”. And here too, Wolff includes certain real-world sites and events to give cultural weight to his representation. For instance, he has marked the site of the Battle of Waterloo, perhaps as a sign of eventual British victory out of apparent defeat, and to tie the pan-European importance of Holmes’s mission in to earlier, historic British endeavours.

There is another, more subtle way, in which Hammer’s writing seems to bring to the fore the fictional world of Sherlock Holmes. We can get an idea of this from the very first page, where the full title of the book is, A Dangerous Game: Being a Travel Guide to the Europe of Sherlock Holmes. It would seem that Hammer has forgotten about Arthur Conan Doyle. This is because Hammer’s travel writing is embedded in a tradition of fan writing known as Sherlockiana, produced by fans of Sherlock Holmes who call themselves Sherlockians. This peculiar fandom is characterised by a practice known as ‘playing the game’: that is the ludic belief that Sherlock Holmes is not a literary character, but was rather a historical figure living at the end of the Victorian period. Hammer does admit that this might seem odd to the uninitiated, when he says at the beginning of A Dangerous Game, “[a]dmittedly, the deliberative confusion of reality with fancy is a supreme idiocy”.

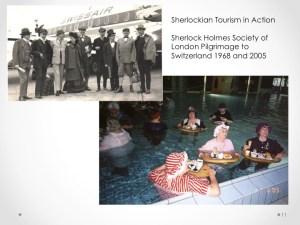

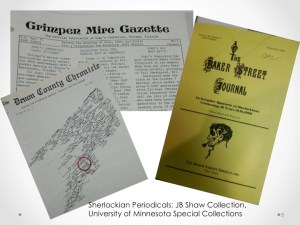

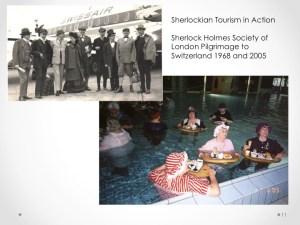

By the time Hammer was writing his guide to the Europe of Sherlock Holmes, in the early 1990s, Sherlockians had been playing the game, primarily in Britain and America but also in many other parts of the world, for more than fifty years. All across America, for instance, fan societies with names such as The Hugo’s Companions, The Reigate Squires or The Midlothian Mendicants produced quarterly periodicals or newsletters with names like The Grimpen Mire Gazette, The Devonshire County Chronicle and The Racing Form that were circulated locally, nationally and internationally to subscribers. We should not forget, of course, the Baker Street Irregulars, the most senior Sherlockian society in America of which all these other societies registered as ‘scions’ or offshoots, and its own quarterly Baker Street Journal. These periodicals featured scholarly articles that often discussed aspects of Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories (known to fans as ‘The Canon’), new pieces of fan fiction, games and puzzles and letters pages in which lively debates about aspects of Holmes and Watson’s lives and times raged. As a senior member of the Baker Street Irregulars and an irregular contributor to the Baker Street Journal, Hammer’s books owe much to the practice of Sherlockiana.

Perhaps the central feature of ‘playing the game’ is denying Doyle his role as author of his stories, and the creator of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson. Displacing Doyle is in fact a prerequisite for fans’ ludic belief in Holmes’s reality. How could Holmes be a real person if he is also the artistic creation of someone else? Yet, the tongue-in-cheek nature of Sherlockiana recognises at the same time the historical role that Doyle played in bringing Holmes to public prominence. Thus Sherlockians accommodate Doyle in their histories by referring to him as “Watson’s friend and literary agent”, or simply as “the literary agent”. In this way they effect a double-displacement for Doyle: from his authorial role and from his own name. By including Doyle in their fandom, albeit out of place, Sherlockians have recognised that playing the game is characterised not, as Hammer put it, by the deliberative confusion of reality with fancy, but rather by their deliberate blurring. Hammer notes this himself further on in his introduction to A Dangerous Game, when he writes of the locations featured in his book, “there are those who claim they were visited not by Holmes but by his biographer or, God save the mark, by his literary agent, and no one can gainsay at this remove which is true”.

So already we can see that while it might look like Hammer is straightforwardly exploring the world of Sherlock Holmes as a fictional world, it is actually rather more complicated. Fact and fiction support and deny each other in equal measure. Hammer is not interested in Doyle’s life and times as a way to understand Holmes’s world, yet he needs to recognise Doyle’s attachment to the books, because that bolsters his Sherlockian belief that Holmes was real. If Doyle was the literary agent, who got Watson’s narratives into print, it explains how Holmes could have actually lived and, at the same time, appeared in books with Doyle’s name stamped all over them. In A Dangerous Game, Doyle appears as a spectre at the du Sauvage hotel in Meiringen, near the Reichenbach Falls. Hammer writes that, “Some years ago, I concluded that the Englisher Hof [the hotel mentioned in The Final Problem] was the du Sauvage, largely on the basis of the English Chapel”. Hammer must have known that this was the hotel at which Doyle and his ailing first wife, Touie, stayed on their trip to Switzerland in 1891, the very trip where Doyle had the idea for Holmes’s death scene at the Falls. Yet to admit this would be to shake the edifice on which Holmes as heritage is built.

Moving the fault lines: blending fact and fiction, history and experience

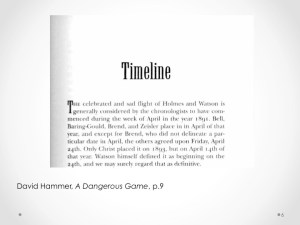

The main effect of Hammer displacing Doyle from history into fiction is that he is then free to move Holmes and Watson from fiction into fact. Throughout his travel writing Hammer implies that Watson actually wrote the stories he is discussing. The logical step for Hammer to take, which he does take, is to accept that these stories, written by a real man about the life of another, real man, are a form of historical record. We can see this quite clearly when Hammer begins his section on ‘The Withdrawal’ with a short chapter on the ‘Timeline’ of events. Like earlier chronologists of Holmes’s life, such as Jay Finley Christ or William Baring-Gould, Hammer is quite demanding with the texts in looking to pin down Holmes and Watson’s movements to set dates. For instance, in summarising Holmes and Watson’s journey between Brussels and Strasbourg, Hammer writes that, “Moving on the third day to Strasbourg, which is what Watson reported. They should have arrived there on the 28th [of April 1891, that is], but Watson inconsistently places them in Strasbourg on Monday the 27th”. Later, he declines to guess at the length of the pair’s stay in Geneva for, “we have no hard information and insufficient data from which to extrapolate”. In treating the text of The Final Problem, which he describes as Watson’s writings, as historical fact, Hammer reflects the wider trend in Sherlockian attitudes towards these stories. Fellow Sherlockian Les Klinger neatly captured this when he described the stories as a “true record” of Holmes’s life.

Hammer further shifts the fault line between fact and fiction, by using a variety of real-world data to build up his representation of Sherlockian Europe. Unlike earlier explorers of Sherlockian geography, whom Robinson and Andersen would categorise as “tourists of the mind” who recognise the primacy of the fictional world, Hammer was not content to sit at home and pour over atlases. He went out into the world to see the sites for himself. As he wrote at the beginning of A Dangerous Game, “for the site-maven… the research must be confirmed or negated by physical inspection. There must be both search and research”. This is because Hammer’s main interest is in expanding the geography of the world of Sherlock Holmes beyond the confines of Doyle’s page; by filling the many gaps left around the edges of the text. In every place he visits, Hammer’s first move is to ask “where did Holmes and Watson stay, and what did they do there?”. To answer this question Hammer relies on a variety of evidence, including real-world texts and materials, Sherlockian assumptions about Holmes’s life, and his own movement through the landscape.

Chief among the real-world materials are Hammer’s trusty contemporary Baedeker guidebooks. Important to Hammer’s quest for Sherlockian heritage is the possibility that, “The flavour of the place and the time can still be extracted”. This is because for the Sherlockian tourist, “the ambiance is as important as the analysis”. Baedeker’s guides, with their historical information, their prices in pounds, shillings and pence and the clues they provide to the travelling habits of late-Victorian bourgeoisie, are a vital tool for Hammer to extract the flavour of the place and time of Sherlockian Europe. Other material artefacts Hammer uses include the hotel buildings themselves: whether they seem to be of the right period and design is an important factor in their selection as a Sherlockian site.

In an example from the chapter on Brussels, for instance, we can see this triangulation process at work, involving all these forms of extra-textual, real-world evidence. Hammer starts by comparing the hotel offerings recorded in Baedeker with his understanding of Holmes’s preferences. He writes, “Baedeker for the appropriate period lists two hostelries in Brussels which would have possessed undeniable English appeal”. These are the Grand Hotel Britannique and Culliford’s English Hotel. “Either of these places”, says Hammer, “would have offered the requisite Anglophile amenities. Holmes was not one of those who would have been impressed by staying behind… the royal palace, and his clear preference had always been for inns”. After this process of negotiation between Baedeker and the portrait of Holmes offered by Doyle and other writes, Hammer declares, “I believe that there is no question but that he would have selected Culliford’s, if only because it was less pretentious”. Finally, Hammer confirms his ‘identification’ of this Holmesian site two pages later when he sees the building itself. He writes, “perhaps it was the rain which gave a sodden aspect to the buildings. Culliford’s English Hotel was no longer there, but the building was, and it was unmistakably what the Belgians thought was English”.

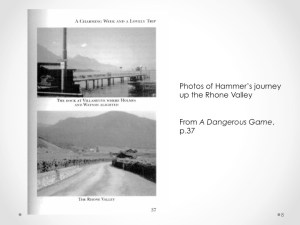

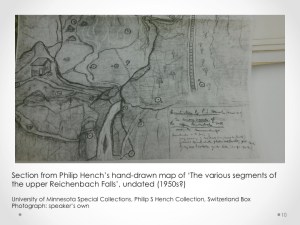

As we can see from this last example, a key piece of evidence in Hammer’s quest to define the geography of Holmes’s Europe is his own movement through it. He collates data from a variety of sources, historical and contemporary, fictional and factual. But the final analysis lies with his ability to walk the supposed route, travel on a particular train or see, possibly go inside, a certain hotel. A very good example of this is his approach to unpacking the route taken, and sites visited, during Holmes and Watson’s week-long tour of the Rhone Valley. Hammer quotes the relevant passage from Doyle’s story in his discussion of timelines, when he quotes Watson saying, “For a charming week we wandered up the valley of the Rhone, and then… we made our way over the Gemmi Pass… and so by way of Interlake to Meiringen”. There is a problem here, says Hammer, in that the agreed dates of this trip allow only four days between the pair leaving Geneva and arriving in Meiringen, near the Reichenbach Falls. Hammer’s solution is to walk the route himself. His record of this experiment, in a chapter called, “A charming week and a lovely trip”, shifts the balance of evidence away from Doyle’s texts more heavily on to Baedeker and Hammer’s own experience of the terrain.

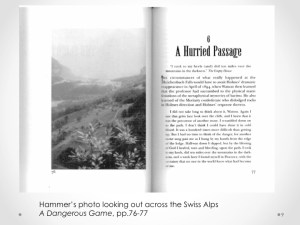

In another, later example, Hammer tries to solve the puzzle of which path Holmes took over the Alps, when getting away from Colonel Sebastian Moran after his tussle at the Falls. In Doyle’s story The Adventure of the Empty House, all that Holmes tells Watson is, “I took to my heels, did ten miles over the mountains in the darkness, and a week later I found myself in Florence, with the certainty that no one in the world knew what had become of me”. Before arriving at the Falls Hammer had made up his mind that there was only one possible route by which Holmes could have escaped: by continuing on the only path from Meiringen to Rosenlau. Yet, he notes that another Sherlockian fan suggested Holmes took the Grimsel Pass. There was only one thing for it: as Hammer writes, “I recognised that the matter could never be definitively resolved unless I could make enquiries in situ and to walk it myself”. Both these examples indicate that for Hammer, the self-professed “site-maven”, the world of Holmes is not entirely fictional, it is contaminated at every point with real-world evidence, and demands to be lived in as much as to be read about.

Conclusion

So now I really should draw these strands together. In this paper I have attempted to show that David Hammer’s Dangerous Game is an example of literary tourism and travel writing that breaks the mould. Rather than being prompted by an interest in the life and times of a favourite author, Hammer, in the tradition of Sherlockian fandom, consciously writes Doyle out of literary history and into the world of Sherlock Holmes. And instead of seeking a deeper engagement with a favourite book, and trying to get a greater connection with the fictional world it creates, Hammer treats the Sherlock Holmes stories as starting points, as historical sources, blurring the boundary between fiction and fact, and between history and his own experiences.

This blurring points towards one of the claims I am making here today: that Hammer’s work represents a particularly lively form of literary tourism. Of course, the relationship between text and tourism is complex; often tourist-readers experience literary sites as additions or expansions to texts; otherwise, as Robinson and Andersen say, they can experience reading as a kind of tourism: by travelling to fictional worlds. But for Hammer, literary tourism rather becomes a kind of reading; an innovative way to engage with the text. Because not only does Hammer walk in the footsteps of Holmes; his co-production of Holmes’s world, through the discovery of new sites and the reinterpreting of Holmes’s activities through real-world artefacts and knowledges, means that Holmes begins to walk in Hammer’s footsteps, too. In his own way, Hammer, like a good Sherlockian, keeps the master alive; his own way involves walking through his world.

Finally, by placing the fault lines of fact and fiction and of history and present in unexpected places, Hammer’s travel writing creates a new form of intangible, transatlantic heritage. By reading the European landscape through the Sherlock Holmes stories, and by investing in the belief that Holmes was not a character of fiction but rather a Victorian man, Hammer produces new geographical knowledges that sit on the borders of myth and of history. It is here, of course, that heritage is born. But this particular heritage is not devoted to a nation or a telling of history: it is the inheritance of the Sherlockians, those fans of Sherlock Holmes, those who believe in the stories as “true records of one man’s life”. This particular community transcends national boundaries and, as Hammer, an American in Europe, demonstrates, transcends the oceans too.